Antarctica has a vast, entirely concealed mountain range. New data reveals its origin over 500 million years ago

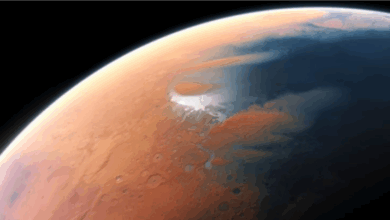

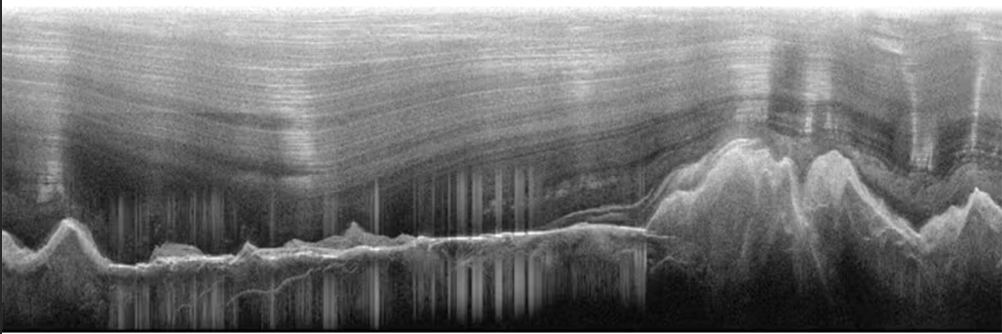

Have you ever imagined what Antarctica looks like beneath its dense cover of ice? Hidden below are rugged mountains, gorges, slopes, and plains.

Some peaks, like the towering Transantarctic Mountains, emerge above the ice. But others, like the enigmatic and ancient Gamburtsev Subglacial Mountains in the heart of East Antarctica, are completely submerged.

The Gamburtsev Mountains are equivalent in magnitude and appearance to the European Alps. But we can’t see them because the high alpine peaks and deep glacial valleys are entombed beneath kilometers of ice.

How did they come to be? Typically, a mountain range will develop in areas where two tectonic plates collide with each other. But East Antarctica has been tectonically stable for millions of years.

Our new study, published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, reveals how this concealed mountain chain arose 500 million years ago when the supercontinent Gondwana formed from colliding tectonic plates.

Our findings offer fresh insight into how mountains and continents evolve over geological time. They also help explain why Antarctica’s interior has remained remarkably stable for hundreds of millions of years.

A concealed secret

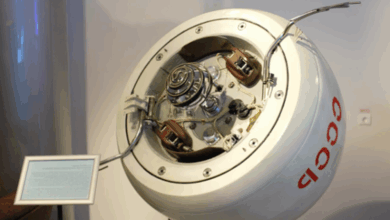

The Gamburtsev Mountains are submerged beneath the highest point of the East Antarctica ice sheet. They were first discovered by a Soviet expedition using seismic techniques in 1958.

Because the mountain range is entirely covered in ice, it’s one of the least understood tectonic features on Earth. For scientists, it’s profoundly perplexing. How could such a vast mountain range form and still be conserved in the core of an ancient, stable continent?

Most main mountain chains identify the locations of tectonic collisions. For example, the Himalayas are still ascending today as the Indian and Eurasian continents continue to converge, a process that began about 50 million years ago.

Plate tectonic models suggest the crust now creating East Antarctica came from at least two large continents more than 700 million years ago. These continents used to be separated by a massive ocean basin.

The collision of these landmasses was crucial to the creation of Gondwana, a supercontinent that included what is now Africa, South America, Australia, India, and Antarctica.

Our new analysis supports the notion that the Gamburtsev Mountains first formed during this ancient collision. The colossal collision of continents triggered the flow of heated, partly liquid rock deep beneath the mountains.

As the crust thickened and heated during mountain construction, it ultimately became unstable and began to disintegrate under weight.

Deep beneath the surface, heated minerals began to flow sideways, like toothpaste squeezed from a tube, in a process known as gravitational spreading. This caused the mountains to partially collapse while still preserving a thick crustal “root,” which extends into Earth’s mantle beneath.

Crystal time recorders

To piece together the chronology of this dramatic rise and decline, we analyzed minuscule zircon grains discovered in sandstones deposited by rivers streaming from the ancient mountains more than 250 million years ago. These sandstones were recovered from the Prince Charles Mountains, which protrude out of the ice hundreds of kilometers distant.

Zircons are often dubbed “time capsules” because they contain infinitesimal quantities of uranium in their crystal structure, which decays at a known rate and allows scientists to determine their age with precision.

These zircon grains preserve a record of the mountain-building timeline: the Gamburtsev Mountains began to rise around 650 million years ago, reached Himalayan heights by 580 million years ago, and experienced profound crustal melting and flow that ended around 500 million years ago.

Most mountain ranges formed by continental collisions are eventually worn down by erosion or altered by subsequent tectonic processes. Because they’ve been preserved by a deep stratum of ice, the Gamburtsev Subglacial Mountains are one of the best-preserved ancient mountain belts on Earth.

While it’s presently very challenging and expensive to drill through the dense ice to sample the mountains directly, our model offers new predictions to guide future exploration.

For instance, recent fieldwork near the Denman Glacier on East Antarctica’s coast uncovered rocks that may be related to these ancient mountains. Further analysis of these geological samples will help reconstruct the concealed architecture of East Antarctica.

Antarctica remains a continent full of geological mysteries, and the secrets concealed beneath its ice are only beginning to be revealed.